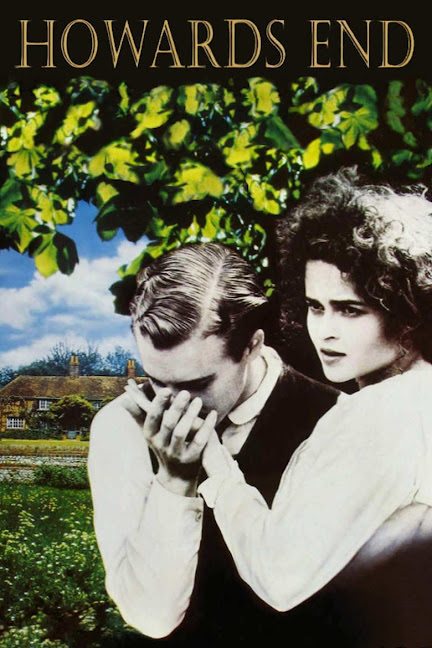

HOWARDS END (1992) ★ ★ ★ ★ ★

I should begin with a confession: I have a soft spot for period pieces. Director James Ivory and producer Ismail Merchant made the best of them in the eighties and nineties, having been partners in both the movie business, and in life. Merchant-Ivory Productions released 44 films, but none are as prescient to an audience in 2022 as the 1992 romantic drama, "Howards End."

The film, based on the 1910 novel of the same name by E.M. Forster, brings Forster's themes of class prejudices and social injustices to life. But to stop there would be akin to saying a clicker brings a TV to life; James Ivory's vision for this picture is so brimful with lush color and vivid beauty, that I marvel at how he made a priceless masterpiece of every shot on a budget of $8 million. "Howards End" is a stunning film.

But his genius, and that of screenwriter Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, transcends imagery. "Howards End" reminds me of Woody Allen's joke about how England would be a nice place to visit, if it weren't for the language barrier. Prawer's dialogue is pitch perfect, spoken by characters who understand the words they're exchanging, but not the language they're exchanging them in. It's a story about three families from each class of Edwardian London (working, middle, and upper) coming together via fateful coincidences, and whose disparate backgrounds and values render meaningful communication all but impossible.

One family in question are the upper middle-class Schlegels, comprised of sisters Margaret (Emma Thompson) and Helen (Helena Bonham Carter), their brother Tibby (Adrian Ross Magenty), and Aunt Juley (Prunella Scales). Margaret is a pragmatist with enlightened views on marriage and love, believing the former is best when predicated on the latter, an avant-garde sentiment in the 1900s. When she learns by letter that her sister is engaged to one of the wealthy Wilcoxes, she responds to Aunt Juley's excitement by declaring that she isn't interested in family pedigree and social standing. The most important thing to her is that her sister is in love.

Helen isn't as sanguine on the matter, and calls off her engagement before Aunt Juley has a chance to meet the chap and give her blessings. The incident is Margaret's chance to renew her acquaintance with the Wilcoxes, and especially the matriarch, Ruth Wilcox (Vanessa Redgrave), whom she met when both families were in Germany. Here, the film warmly illuminates the fierce bonds of friendship that form between women. Ruth, who decries the growing sprawl of London and the demolition of old homes, expresses horror upon hearing that the Schlegels will be forced to move from theirs when their lease is up. She tells Margaret of her ancestral house in the country, a beautiful brick cottage called Howards End.

Ruth is seriously ill, but her fondness for Margaret carries through the final stage of her life, until alone on her deathbed she scribbles her last wish on a piece of paper. It's a wish that makes Henry (Anthony Hopkins), her widower husband, very unhappy. He and the other Wilcoxes wrongly keep it to themselves. Middle-aged and alone in a massive house, Henry develops an attraction to Margaret, and proposes to her. The two are soon after married.

In the interim, Helen unwittingly draws a young man named Leonard Bast (Samuel West) into the Schlegels' affairs by accidentally taking his umbrella. Leonard is a poor insurance clerk who lives with wife Jacky (Nicola Duffett) in a flat near the train tracks. He pursues his umbrella, and there are gentle sparks between him and Helen that are skillfully brushed into their looks and awkward pauses. Later in the film, when Helen chastises him and calls him a "noodle," there's more sexual firepower in that one word than in all 125 minutes of "Fifty Shades of Grey." These deftly-played inhibitions generate a surprising level of eroticism, a refreshing change of pace in our present age of gratuitous sex and foul language.

Leonard is also a dreamer, and wanders from London into the countryside at night. When questioned, he claims that he doesn't know why he wanders. Margaret asks him where his family is from, and he tells her they were agricultural workers from around Shropshire. Ever the pragmatist, she says, "You see? It was ancestral voices calling you." But it wasn't ancestral voices, and it has nothing to do with a calling. All of Leonard's reasons are sitting next to Margaret in a buttoned-up corset.

The sisters share with him advice from Henry that he should leave his job before his company goes under, as Henry seems to think it will. The young man takes the advice, but the company he transitions to goes under instead, and he's unable to return to his former employer, which Henry later says has turned things around, and has a solid future. Mortified and convinced that his advice has impoverished Leonard, Helen demands that Henry do something to set things right for the Basts. But it's too late; Margaret has already married into the Wilcox name, and thus has climbed the social ladder to its highest rung. Helen must not put blame on her sister's husband and endanger their marriage, and her future.

Eventually we learn that Helen is in love with Leonard, and when she shares a passionate moment with him on a rowboat, the implications for the union of the Schlegel and Wilcox families get even shakier. Much of this narrative tension stems from the rigid and morally opaque personality of Henry Wilcox. Hopkins plays him as an uncultivated rich man with a self-styled patina of the erudite, a mark of the character's personal insecurities. A moment in which he sits on one of Margaret's books deftly reveals his psyche, which his wife ruefully understands. He dislodges it from the seat cushion, peers at its cover, and says, "What's this? What've you been reading now? Theo - ?"

"Theosophy," Margaret says.

"Ah, yes. Madame Blavatsky. Now, what a clever little woman it is. You see, that's what I mean about Helen. She reads these things, and her mind gets addled. Our Margaret, she keeps her facts straight."

"What facts are those, dear?"

"About men and women, and all that sort of thing. Who is who, and what is what." He points to a picture in the book, veiling confusion with an air of curiosity. "Now what is that?"

It's all of Henry in those last lines: Men have their place, and women have theirs. The rich are rich, and the poor are poor. Who is who, and what is what. But that isn't how Margaret sees it. Emma Thompson's adroit portrayal of a woman desperate to preserve her marriage while navigating her husband's callous lack of empathy for others is brilliant - it earned her an Oscar, after all. She emanates a growing sense of concern for her sister, who fled without explanation to Germany after her encounter with Leonard, sending only postcards. Helen avoids seeing her siblings when she returns, which prompts Henry to suggest they invite her to stop by Howards End, where her belongings are in storage, and where Margaret can meet her.

In this remarkable scene, the "language barrier" between Margaret and Henry, two people whose values and moral compasses could not be further apart, is elucidated. Henry tells Margaret that she can assess if Helen is mentally stable, and if not, the car is right outside, and they can whisk her away to a "specialist." Margaret tells him that would be impossible. Henry, barely listening, asks her why. "Because, Helen and I, we don't speak that particular language, if you see my meaning," she says.

In "Howards End," meaning is everything. The meaning of family, and the earthly things that tie us to our pasts. The meaning of romantic passion, inside and outside the confines of marriage. The meaning of forgiveness, and of holding grudges. The meaning of having empathy for those who have less than we do, and of the enmity that arises from the chasm between the rich and the poor. And perhaps most importantly, the meaning of a woman's dying wish, and the perils that ensue when a family fails to honor it.

--- Bill Fontaine